|

|

|

A. Prerepublican Era

The first government of Pakistan was headed by Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah as governor-general, and it chose Karachi as its capital. From 1947 to 1951 the country functioned under chaotic conditions. The government endeavored to create a new national capital, organize the bureaucracy and the armed forces, resettle refugees, and contend with provincial politicians who often defied its authority.

After Liaquat was assassinated in 1951, Khwaja Nazimuddin, an East Pakistani who had been governor-general since Jinnah's death in 1948, became prime minister. Unable to prevent the erosion of the Muslim League's popularity in East Pakistan, however, he was forced to yield to another East Pakistani, Muhammad Ali Bogra, in 1953. When the Muslim League was nevertheless routed in East Pakistani elections in 1954, the governor-general dissolved the constituent assembly as no longer representative. The new assembly that met in 1955 was not dominated by the Muslim League. Muhammad Ali Bogra was then replaced by Chaudhri Mohammad Ali, a West Pakistani. At the same time, General Iskander Mirza became governor-general.

The new constituent assembly enacted a bill, which became effective in October 1955, integrating the four West Pakistani provinces into one political and administrative unit. The assembly also produced a new constitution, which was adopted on March 2, 1956. It declared Pakistan an Islamic republic. Mirza was elected provisional president.

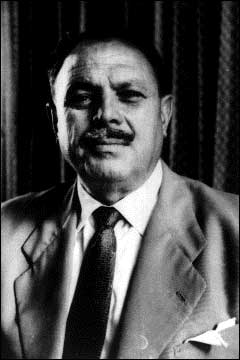

Four governments were changed from 1956-1958. Political instability led to martial law in 1958, declaring Field Martial General Muhammad Ayub Khan first Martial Law Administrator and President of Pakistan.

B. The Ayub Years

Ayub ruled Pakistan almost absolutely for more than ten years, and his regime made some notable achievements, although it did not eliminate the basic problems of Pakistani society. A land reforms commission appointed by Ayub distributed some 900,000 hectares (about 2.2 million acres) of land among 150,000 tenants. The reforms, however, did not erase feudal relationships in the countryside. Ayub's regime also increased developmental funds to East Pakistan more than threefold. This had a noticeable effect on the economy of the eastern part, but the disparity between the two sectors of Pakistan was not eliminated.

Ayub ruled Pakistan almost absolutely for more than ten years, and his regime made some notable achievements, although it did not eliminate the basic problems of Pakistani society. A land reforms commission appointed by Ayub distributed some 900,000 hectares (about 2.2 million acres) of land among 150,000 tenants. The reforms, however, did not erase feudal relationships in the countryside. Ayub's regime also increased developmental funds to East Pakistan more than threefold. This had a noticeable effect on the economy of the eastern part, but the disparity between the two sectors of Pakistan was not eliminated.

Perhaps the most pervasive of Ayub's changes was his system of Basic Democracies. The Basic Democratic System had four tiers of government from the national to the local level, and each tier was assigned certain responsibilities in administering the rural and urban areas, such as maintenance of elementary schools, public roads, and bridges.

Ayub also promulgated an Islamic marriage and family laws ordinance in 1961, imposing restrictions on polygamy and divorce and reinforcing the inheritance rights of women and minors.

For a long time Ayub maintained cordial relations with the United States, stimulating substantial economic and military aid to Pakistan. This relationship deteriorated, however, in 1965, when another war with India broke out over Kashmir. The USSR intervened to mediate the conflict, inviting Ayub and Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri of India to Toshkent. By the terms of the so-called Toshkent Agreement of January 1966.

C. Civil War

Ayub resigned in 1967 over the dispute of unsatisfied election results of 1965. Gen Yahya sworn in. In an attempt to make his martial-law regime more acceptable, Yahya dismissed almost 300 senior civil servants and identified 30 families that were said to control about half of Pakistan's gross national product. To curb their power Yahya issued an ordinance against monopolies and restrictive trade practices in 1970. He also made commitments to transfer power to civilian authorities, but in the process of making this shift, his intended reforms broke down.

Ayub resigned in 1967 over the dispute of unsatisfied election results of 1965. Gen Yahya sworn in. In an attempt to make his martial-law regime more acceptable, Yahya dismissed almost 300 senior civil servants and identified 30 families that were said to control about half of Pakistan's gross national product. To curb their power Yahya issued an ordinance against monopolies and restrictive trade practices in 1970. He also made commitments to transfer power to civilian authorities, but in the process of making this shift, his intended reforms broke down.

The greatest challenge to Pakistan's unity, however, was presented by East Pakistan, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, leader of the Awami League, who insisted on a federation under which East Pakistan would be virtually independent. He envisaged a federal government that would deal with defense and foreign affairs only; even the currencies would be different, although freely convertible. His program had great appeal for many East Pakistanis, and in the election of December 1970 called by Yahya, Mujib, as he was generally called, won by a landslide in East Pakistan, capturing a clear majority in the National Assembly. Bhutto's Pakistan People's Party (PPP) emerged as the largest in West Pakistan.

Suspecting Mujib of secessionist politics, Yahya in March 1971 postponed indefinitely the convening of the National Assembly. Mujib in return accused Yahya of collusion with Bhutto and established a virtually independent government in East Pakistan. Yahya opened negotiations with Mujib in Dhaka in mid-March, but the effort soon failed. Mujib was arrested and brought to West Pakistan to be tried for treason. Meanwhile Pakistan's army went into action against Mujib's civilian followers, who demanded that East Pakistan become independent as the nation of Bangladesh.

There were a great many casualties during the ensuing military operations in East Pakistan, as the Pakistani army attacked the poorly armed population. India claimed that nearly 10 million Bengali refugees crossed its borders, and stories of West Pakistani atrocities abounded. The Awami League leaders took refuge in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and established a government in exile. India finally intervened on December 3, 1971, and the Pakistani army surrendered 13 days later. On December 20, Yahya relinquished power to Bhutto, and in January 1972 Bangladesh established an independent government. When the Commonwealth of Nations admitted Bangladesh later that year, Pakistan withdrew its membership, not to return until 1989. However, the Bhutto government gave diplomatic recognition to Bangladesh in 1974.

D. The Bhutto Government

Under Bhutto's leadership a diminished Pakistan began to rearrange its national life. Bhutto nationalized the basic industries, insurance companies, domestically owned banks, and schools and colleges. He also instituted land reforms that benefited tenants and middle-class farmers. He removed the armed forces from the process of decision making, but to placate the generals he allocated about 6 percent of the gross national product to defense. In 1973 the National Assembly adopted the country's fifth constitution. Bhutto became prime minister, and Fazal Elahi Chaudry replaced him as president.

Under Bhutto's leadership a diminished Pakistan began to rearrange its national life. Bhutto nationalized the basic industries, insurance companies, domestically owned banks, and schools and colleges. He also instituted land reforms that benefited tenants and middle-class farmers. He removed the armed forces from the process of decision making, but to placate the generals he allocated about 6 percent of the gross national product to defense. In 1973 the National Assembly adopted the country's fifth constitution. Bhutto became prime minister, and Fazal Elahi Chaudry replaced him as president.

Although discontented, the military remained silent for some time. Bhutto's nationalization programs and land reforms further earned him the enmity of the entrepreneurial and capitalist class, and the religious elements saw in his socialism an enemy of Islam. His decisive flaw, however, was his inability to deal constructively with the opposition. His rule grew heavy-handed. In general elections in March 1977 nine opposition parties united in the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) to run against Bhutto's PPP. Losing in three of the four provinces, the PNA alleged that Bhutto had rigged the vote. The PNA boycotted the provincial elections a few days later and organized demonstrations throughout the country that lasted for six weeks.

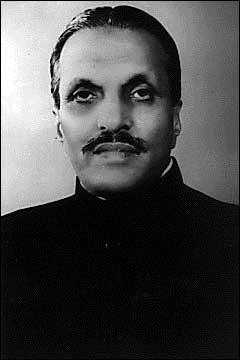

E. Zia Regime

When the situation seemed to be deadlocked, the army chief of staff, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, staged a coup on July 5, 1977, and imposed another martial-law regime. Bhutto was tried for political murder and found guilty; he was hanged on April 4, 1979.

When the situation seemed to be deadlocked, the army chief of staff, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, staged a coup on July 5, 1977, and imposed another martial-law regime. Bhutto was tried for political murder and found guilty; he was hanged on April 4, 1979.

Zia formally assumed the presidency in 1978 and announced that Pakistan's laws should conform to Islamic law. The constitution of 1973 was amended accordingly in 1979, and Sharia (Islamic law) courts were established to exercise Islamic judicial review. Interest-free banking was initiated, and maximum penalties were provided for adultery, defamation, theft, and consumption of alcohol.

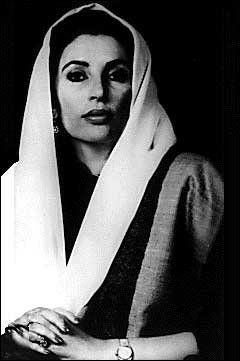

On March 24, 1981, Zia issued an order for a provisional constitution, operative until the lifting of martial law in the future. It envisaged the appointment of two vice presidents and allowed political parties approved by the election commission before September 30, 1979, to function. All other parties, including the PPP, now led by Bhutto's widow and daughter, were dissolved.

Pakistan was greatly affected by the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in December 1979; by 1984 some 3 million Afghan refugees were living along Pakistan's border with Afghanistan, supported by the government and by international relief agencies. In September 1981 Zia accepted a six-year economic and military aid package (worth \$3.2 billion) from the United States. After a referendum in December 1984 endorsed Zia's Islamic-law policies and the extension of his presidency until 1990, Zia permitted elections for parliament in February 1985. A civilian cabinet took office in April, and martial law ended in December. Zia was dissatisfied, however, and in May 1988 he dissolved the government and ordered new elections. Three months later he was killed in an airplane crash possibly caused by sabotage, and a caretaker regime took power.

F. Recent Developments

A civil servant, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, was appointed president, and Bena

A civil servant, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, was appointed president, and Bena